Introduction

Oral anticoagulants have become a commonly prescribed medication for multiple disease states such as atrial fibrillation, non-native heart valves and cerebral vascular diseases for primary and secondary prevention of arterial and venous thromboembolism. Bleeding caused by oral anticoagulants continues to be the predominant complication with risk for significant sequelae. Oral anticoagulant adverse events cause more emergency department visits than any other medication class and as the population continues to age, the incidence of anticoagulation related bleeding is expected to increase.1

Four-factor Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (4F-PCC) contains coagulation factors II, VII, IX, X and proteins C and S, which provides the necessary clotting factor support to achieve hemostasis.2–5 Various guideline recommendations support the administration of 4F-PCC for reversal of bleeding caused by both warfarin and direct factor Xa inhibitors (FXai).6,7 The 4F-PCC products available in the United States (Kcentra®, CSL Behring and Balfaxar®, Octapharma) recommend all doses be administered at a rate of 0.12 mL/kg/min (~3 units/kg/min), with a maximum rate of 8.4 mL/min (~210 units/min).8,9 Using the recommended administration rate, the maximum dose (5,000 units) takes approximately twenty-four minutes to be infused.

The package insert for 4F-PCC contains a warning regarding hypersensitivity reactions and instructions to immediately discontinue the medication if a severe allergic reaction or anaphylactic type reaction occurs.8,9 However, no hypersensitivity reactions were reported in the pivotal clinical studies and this warning is based on postmarketing reports collected through the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System.10 Because these reports do not provide a denominator for exposure, the true incidence of hypersensitivity reactions with 4F-PCC cannot be estimated, and no published rate is available.

In 2013, our Level 1 trauma center approved and added 4F-PCC to our medication formulary with an administration rate of 20 mL/min based on prior European studies where patients received infusions at speeds up to 10 units/kg/min and 42.7 mL/min.11–17 In all areas of the hospital, 4F-PCC doses are prepared at bedside and given in multiple syringes as an intravenous (IV) push dose. By utilizing this method, a 5,000 unit dose (200 mL) can now be administered over approximately 10 minutes. Given the paucity of data available on increased infusion rates of 4F-PCC, this study aims to perform a review of the hypersensitivity effects of 4F-PCC when administered at a rate of 20 mL/min as an IV push.

Methods

This was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients at a Level 1 trauma center who received 4F-PCC for reversal of an emergent bleed while on oral anticoagulation. Local Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Adult patients with a history of taking either warfarin or a FXai (apixaban, rivaroxaban, or edoxaban) admitted to either the Emergency Department or general hospital and needing emergent reversal between January 1, 2013 and January 1, 2023 were included. Patients were excluded if they had a documented allergy to 4F-PCC, received 4F-PCC at an outside hospital prior to transfer (or missing pre-hospital documentation with inability to confirm administration) or progression to comfort focused measures within 24 hours. In addition, all protected patient classifications were excluded.

Fourfactor PCC was dosed based on the category of anticoagulation the patient was taking. For patients on warfarin, International Normalized Ratio (INR) measurements were obtained and 4F-PCC dosed in accordance with the result (25 units/kg for INR 2 to <4 [max of 2,500 units], 35 units/kg for INR 4 to <6 [max of 3,500 units], and 50 units/kg for INR >6 [max of 5,000 units]). For patients taking a FXai, or if the specific anticoagulation type could not be confirmed prior to administration, a dose of 50 units/kg (max of 5,000 units) was utilized. All doses of 4F-PCC were procured from the inpatient pharmacy and prepared by a pharmacist at the patient’s bedside in 50 mL or 60 mL syringes, depending on supply availability. The number of syringes prepared was determined by the dose of 4F-PCC required for reversal (maximum of five syringes). Each syringe was administered by a nurse whose dedicated role included medication administration during the resuscitation. Repeat INR values were collected thirty minutes post 4F-PCC administration for patients treated for warfarin reversal.

The primary outcome was development of an infusion reaction within one hour of 4F-PCC administration as defined by either receipt of rescue medications (e.g. epinephrine, histamine receptor antagonists, steroids or nebulized bronchodilators), requirement of escalating respiratory support or written documentation of infusion reaction (e.g. erythema, swelling, or hypotension with Mean Arterial Pressure [MAP] less than 65 mmHg requiring vasoactive support).

Secondary outcomes included post reversal INR to <2 and <1.5 after receipt of 4F-PCC for patients taking warfarin and thrombotic complications (Deep Vein Thrombosis [DVT], Superficial Vein Thrombosis [SVT], pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke) within seven days or during hospitalization, which ever was longer.

Results

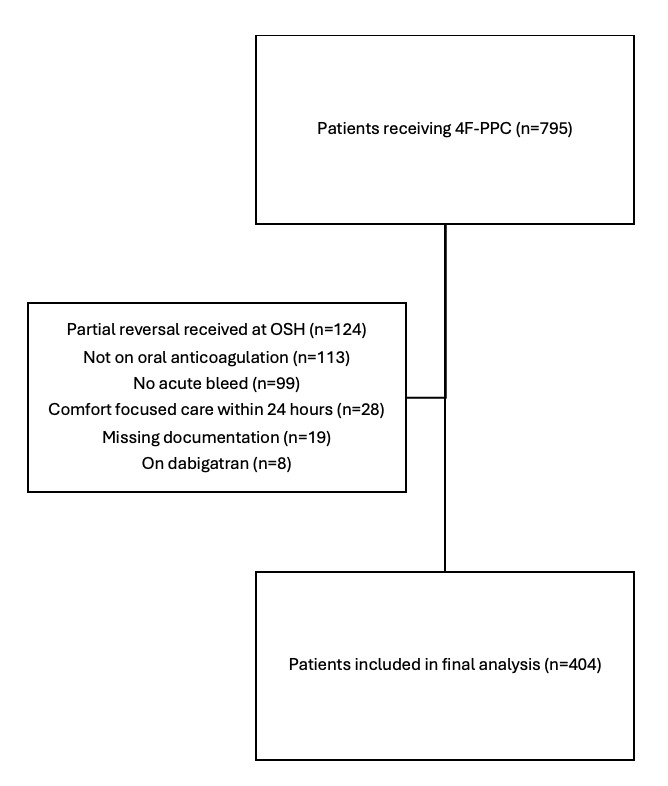

An electronic query of all 4F-PCC administrations between January 1, 2013 and January 1, 2023 returned 795 patients of which 404 were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). The most common reasons for exclusion included receipt of partial anticoagulation reversal prior to transfer to our hospital (n=124), receipt of 4F-PCC for generalized coagulopathy without being on oral anticoagulation (n=113), and reversal for a non-urgent procedure without acute or active bleeding (n=99).

Presenting demographic characteristics as well as anticoagulation and bleed parameters are listed in Table 1. Warfarin was the most commonly used anticoagulant (n=203, 50.2%), followed by apixaban (n=144, 35.6%) and rivaroxaban (n=56, 13.9%). Trauma was the primary mechanism of bleeding (63.1% of patients), with only 36.9% presenting due to a spontaneous bleed. Emergent anticoagulation reversal was most often indicated for an intracranial hemorrhage (n=267, 66.1%), with gastrointestinal (n=39, 9.7%) and intrathoracic (n=22, 5.4%) as other common sites.

A total of six patients (1.5%) received a prespecified rescue medication within one hour of receiving 4F-PCC (Table 2). Four patients had the histamine receptor antagonist famotidine, with two patients receiving inhalers after anticoagulation reversal. Thirty-seven patients (9.2%) required initiation or escalation of their respiratory support after receiving 4F-PCC with the most common modality being supplemental oxygen via either nasal cannula or non-rebreather mask. Twelve patients (2.9%) ultimately required intubation. There was only one documented reaction of erythema that was concerning for a possible infusion reaction, which was noted more than eight hours after 4F-PCC administration. No swelling of any anatomical area was reported.

Thrombotic complications were reviewed within seven days of 4F-PCC administration or hospitalization (whichever was longer), with thirty-nine events recorded. There were 38 episodes of venous thromboembolism (n=33 DVT (8.2%), n=5 SVT (1.2%)) and one arterial thrombus (ischemic stroke) (Table 2). The median time from 4F-PCC administration to development of a thrombotic complication was 73.1 hours (IQR 51.4-110.3 hours).

Of the 203 patients utilizing warfarin as their anticoagulation, post anticoagulation reversal INR values were available for 97.5% (n=198, Table 2). After receiving 4F-PCC, 195 patients (98.5% of warfarin cohort) had a repeat INR of <2.0, with 179 patients (90.4%) reaching an INR of <1.5. Patients taking warfarin were also given phytonadione (n=202, 99.5% of warfarin cohort) to assist in INR reversal in addition to 4F-PCC.

Discussion

Four-factor Prothrombin Complex Concentrate continues to be the standard of care for patients presenting with emergent bleeding secondary to warfarin or FXai. The available 4F-PCC products in the United States have a recommended maximum infusion rate of 8.4 mL/min (~210 units/mL).

Infusion rates greater than manufacturer recommendations began appearing in early studies of 4F-PCC. In 2001, Evans et al. reported on ten patients receiving 30 units/kg of Beriplex® P/N over ten minutes (final rate 3 units/kg/min) for emergent reversal of an INR >8.13 Preston et al. maintained the 4F-PCC infusion time of 10 minutes while increasing the maximum allowed dose of Beriplex® P/N given at this rate to 50 units/kg (final rate 5 units/kg/min).14

Two dosing regimens, 25 units/kg and 40 units/kg, of Octaplex® for patients presenting with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) associated intracranial hemorrhage were evaluated at twenty two centers in France.17 A post hoc analysis of the infusion speeds showed 39 patients (73.5% of cohort) had an infusion speed of ≥8 mL/min (median 10.2 mL/min, IQR 6.9-16 mL/min). The maximum recorded infusion speed was 42.7 mL/min. Additional international studies have reported successful administration of varying 4F-PCC products with rates up to 6.6 units/kg/min and 40 mL/min in small populations.11,12,15,16

Our accelerated infusion rate of 20 mL/min can lead to quicker completion of anticoagulation reversal therapy, with a nearly four-fold reduction in administration time compared to the standard IV infusion when given at the maximum reported 40 mL/min. Since the addition of 4F-PCC to our hospital formulary, all doses are prepared at the bedside and given as an IV push. This delivery method reduces the overall time to anticoagulation reversal therapy completion by removing the medication preparation from the central pharmacy compounding room. This rapid administration rate also avoids placing the dose on an infusion pump, which assists in allowing for other critical medications and resuscitation products to be administered expeditiously when access is limited. The increased speed of anticoagulation reversal therapy can also be beneficial for patients that require an emergent procedure to manage their bleed by hastening transfer to the procedural area.

Hypersensitivity data is not prominently featured in studies evaluating 4F-PCC, despite being listed in the package insert as a possible concern. Rhoney and colleagues studied 528 patients that received Kcentra® for reversal of VKA related intracranial hemorrhages, primarily non-traumatic in origin.18 Only two hypersensitivity reactions were recorded equaling 0.4% of the cohort.

Milling et al. conducted a pharmacovigilance review spanning twenty-six years evaluating the CSL Behring database for spontaneous reports, postmarking studies, reports from regulatory agencies and individual cases analyzing all adverse drug events related to Kcentra® and Beriplex® P/N.19 Anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity/allergic reactions were reported in 36 patients, 5.9% of all cases. This may be affected by underreporting as it is not required to submit adverse events to the manufacturer and is purely voluntary. Literature with increased 4F-PCC administration rates up to 30 mL/min rapid IV push have also found no infusion related adverse events, further supporting elevated speeds.15,20

In our study, six patients had administration of a prespecified rescue medication, with only one actual potential 4F-PCC related infusion reaction documented. When evaluating each rescue medication administration, it was found that all famotidine orders originated from a Trauma Intensive Care Unit admission order set, having no relation to 4F-PCC administration and all inhalers were given on a scheduled basis per home instructions. Only one patient had documented urticaria that was noted 8.78 hours after receipt of 4F-PCC; however, this was also after receiving contrast for an imaging study, confounding the reaction.

The progression of respiratory support, whether to supplemental oxygen or escalation to intubation occurred in thirty-seven (9.2%) of patients. Of these, sixteen were initiated on two liters of oxygen via nasal cannula or open oxygen mask, with eight patients escalated to oxygen flows greater than two liters. Of the twelve patients requiring intubation, four were intubated in the operating room prior to receiving a procedure, with the remainder intubated due to declining mental status related to their intracranial injury. Respiratory support is common in patients that present with intracranial hemorrhages due to alteration of their mentation or aspiration requiring intubation for airway protection as well as the sequelae from other traumatic injuries, including chest wall trauma necessitating oxygen supplementation. After removing unrelated orders and accounting for baseline injuries, our rates of hypersensitivity are in line with prior reports, while recognizing this adverse event is not consistently present in prior literature.

With the intent to decrease the incidence of thromboembolic complications, 4F-PCC is recommended to be administered as an IV infusion.21 Thirty nine patients (9.6%) in our study developed a thromboembolic adverse event after receiving 4F-PCC as an IV push, consistent with previous prospective, randomized, studies of slowly infused 4F-PCC with a thromboembolic adverse event rate of 7-7.8%.4,22,23 Retrospective trials of 4F-PCC have a much wider range of reported thromboembolic events, spanning 0-28.6% across multiple clinical and operational settings, including fixed dosing of 4F-PCC.2,24–28 Prior research of rapid 4F-PCC rates has found no association with higher thrombogenicity marker peak levels or greater cumulation of these markers, with no increase in developed thromboembolic states.12–14,16,17 Our rates of venous thromboembolism (VTE) may have been impacted by our institutional policy that requires all patients admitted for a traumatic injury receive weekly bilateral lower extremity duplexes regardless of symptoms. Of the patients diagnosed with DVT or SVT after 4F-PCC, 61.5% (n=24) were asymptomatic events detected on screening duplex. Prior research involving early screening for DVT after trauma has shown detection rates as high as 13.3% in this population, regardless of anticoagulation reversal, with our rates being in line with this finding.29 While our overall thromboembolic event rate of 9.6% was comparable to prior studies in our population, removing those events identified via screening protocol, our symptomatic event rate is reduced to 3.7%.

At the time the complication was detected, 92.3% of patients were receiving mechanical thromboprophylaxis, with 46.2% of patients additionally having chemical thromboprophylaxis. Our institutional protocol is to hold chemical thromboprophylaxis in patients with intracranial bleeds until forty-eight hours after stable head imaging. Based on this restriction, thirteen patients in which a thromboembolic event occurred were ineligible for chemical thromboprophylaxis at the time of diagnosis.

Our study is not without limitations, primarily its retrospective design with reliance on electronic health record review which has evolved and potentially contributed to missing data. Lack of adjudication of our primary outcome and delineation/removal of events unrelated to the treatment also leads to possible misinterpretation of the results. Our prespecified allergic reaction medications appeared in more order sets and scenarios than we anticipated, confounding the correlation to 4F-PCC administration. Having a two-reviewer process with third-party resolution to determine if outcomes were related to 4F-PCC administration or other confounders would help improve the analysis. We also do not have definitive confirmation regarding the actual administration rate that occurred as human variance could have contributed to infusion rates of faster or even potentially slower than 20 mL/min. Our historical experience would tend to lean towards IV push medications being given faster during high intensity scenarios (including life threatening bleeds), so we feel confident that these administrations only add to the defense of increased infusion speeds for 4F-PCC.

Conclusion

In summary, our institutional experience supports an increased 4F-PCC infusion rate of 20 mL/min as an IV push. We found no evidence of substantially increased definitive hypersensitivity reactions or thromboembolic events. Future randomized trials with standardized infusion times are required to establish non-inferiority and confirm these results.

Conflicts of Interest

None

IRB APPROVAL

Obtained at local institution

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CREDITS

None

FUNDING

None