Case Summary

The patient is a 47-year-old male with a history of spinal cord stimulator implantation and chronic pain following a left distal biceps rupture for which he was taking duloxetine 90 mg daily and pregabalin 100 mg twice daily and recurrent migraines. For management of his migraines, he was prescribed topiramate for about one year for presumed occipital neuralgia, which provided minimal relief. After being off topiramate for about one year, he was restarted on topiramate (patient could not describe the dosage and frequency of his topiramate) therapy in addition to starting rizatriptan 10 mg once at the onset of migraine with a repeated dose in 2 hours if needed. He used rizatriptan for about one week, and had subjective improvement in his symptoms, so he self-discontinued. After about a week of relief, he felt his headache return, so he restarted his rizatriptan therapy by using two doses daily for six days. On the morning of his presentation to the ED, he took two doses of rizatriptan and by noon of that day, he started to notice blurring of his vision, followed by significant brow ache and emesis, prompting him to present in the evening. Prior to this event, his ocular history was benign.

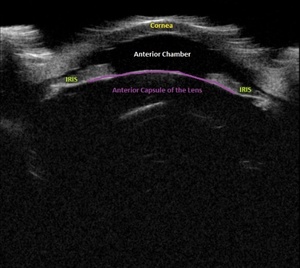

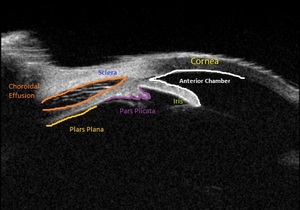

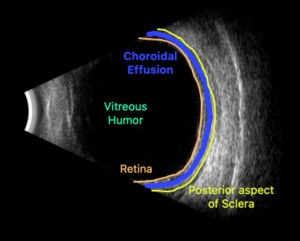

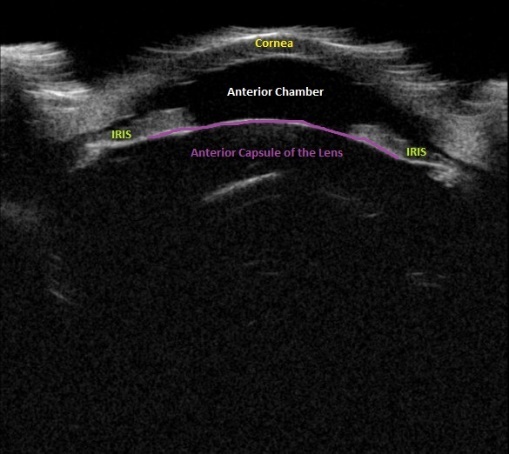

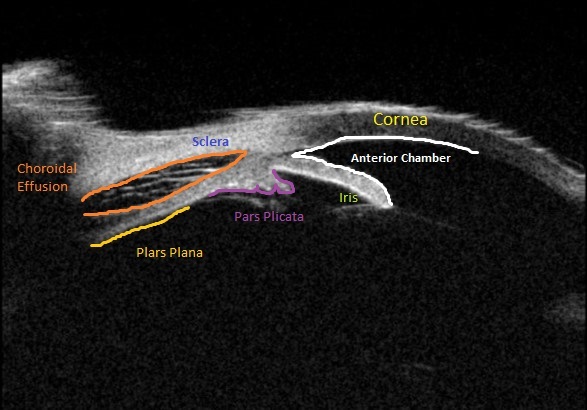

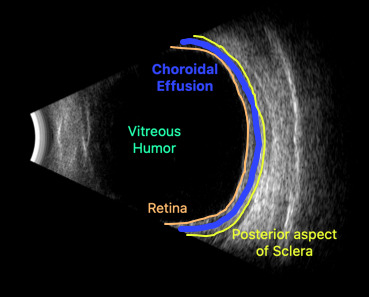

Upon initial evaluation, the patient presented with stable vital signs. His IOP (normal range 10-21 mmHg) was found to be 54 in the right eye, 56 in the left eye. The patient received acetazolamide 250 mg IV and ophthalmology was consulted. Upon evaluation by ophthalmology, the IOP was 34 and 28. The patient was previously emmetropic, but reported persistent blurred vision, and had a manifest refraction of – 3.00 diopters in both eyes in the ED. Visual acuity was assessed with a near card without correction, and found to be 20/25 in the right eye, 20/25 in the left eye. Gonioscopy showed a closed angle in both eyes that could be opened with indentation. There was trace chemosis in the conjunctiva in both eyes, with shallow anterior chambers (Figure 1), and minimal inflammatory cells. The optic nerves appeared perfused, and there were shallow choroidal folds present in the macula. It was felt that his presentation was due to bilateral ciliary body effusion (Figure 2 & 3) causing anterior displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm, closing the angle and leading to this myopic shift.

Pressure lowering drops including 1 drop of both dorzolamide 2%-timolol 0.5% and brimonidine 0.2% were administered in the ED and his IOP returned to 22 in the right eye and 18 in the left eye by the time of discharge. The patient also received a single dose of 500 mg IV methylprednisolone. He was discharged on a regimen on oral acetazolamide and eye drops consisting of brimonidine, and dorzolamide-timolol for IOP, prednisolone acetate for low grade inflammation, as well as atropine for this ciliary body effusion. He was also told to stop his rizatriptan and topiramate.

The patient followed up in the glaucoma clinic the following day on these medications, his IOP was 12/11. His myopic shift was nearly resolved after one day, with refraction of –0.50 diopters in each eye with 20/20 vision. Formal ocular ultrasound and fundus photograph were obtained. By one week after this initial presentation, the myopic shift and choroidal folds had completely resolved, and the patient was told to discontinue all glaucoma medications, and his IOP has remained at physiologic levels off drops. He was ultimately evaluated by a headache specialist who diagnosed him with medication overuse headaches and has not used his rizatriptan or topiramate since.

Discussion

Topiramate and other sulfa-based compounds have been well documented in their ability to cause AAC.1,2 The mechanism is proposed to be from reduction in the depth of the anterior chamber, choroidal effusions, and retinal edema.3 Rizatriptan is one of many “triptan” agents that are currently available that selectively target 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors and is commonly used for abortive migraine therapy. These agents are proposed to interact through a variety of potential mechanisms including increase aqueous humor production and ciliary body swelling causing trabecular meshwork blockage with myopic shift.4 In this case, the patient had been using rizatriptan for abortive migraine treatment before topiramate was added in addition to his home duloxetine therapy. After addition of rizatriptan therapy, in addition to continued use of topiramate and duloxetine, the AAC presentation occurred 11 days later. The Naranjo Algorithm Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale was utilized to look at rizatriptan, topiramate, and duloxetine for this case.5 Rizatriptan scored a 6, topiramate scored a 5, and duloxetine scored a -1 (Table 1). Rizatriptan scored slightly higher than topiramate due to the increased severity of the AAC due to a likely increase in frequency of dosing. Both of these medications fall within the “probable” categorization of the scale suggesting that there is a reasonable likelihood of these medications causing the adverse drug event. Duloxetine, based on a score of -1, was classified as “doubtful,” meaning that it is unlikely to be the cause of the adverse reaction. The patient was continued on the duloxetine following this event and maintains on therapy, giving additional support to its low likelihood of causing ACC in this patient.

Current literature reflects that the presentation of AAC in the setting of topiramate therapy peaks at two weeks but can present anywhere between 1 to 49 days of therapy.3,6 Recent publication of a case of AAC between topiramate and sumatriptan highlights the interaction of these medications and the awareness that is needed by in diagnosing and managing these patients.7 In both the referenced and presented patient case, acetazolamide 250 mg and methylprednisolone 500 mg were given to the patient. In the patient’s case, following the administration of both agents, the patient had a decrease in IOP and subjective improvement in his visual symptoms. These agents may be beneficial in patients presenting with topiramate and triptan induced AAC based on the potential inflammatory mechanisms and increased aqueous humor production.8,9 While this patient did not have the typical risk factors for developing AAC, this case demonstrates the importance to avoid excessive use of triptan therapy, minimize combination therapy between triptan therapy and topiramate, and early identification of this ophthalmic emergency based on medication history.

Conclusion

In the presented case, the reinitiation of topiramate therapy and the extended and high utilization of rizatriptan therapy likely precipitated the patient’s presentation of acute bilateral angle-closure. This case supports the growing evidence of the interaction between topiramate and triptan therapy and the need for providers and pharmacists to consider this in the differential for similarly presenting cases.

IRB Approval

N/A

Funding

The authors did not receive any compensation or support for the submitted work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There was no funding related to this case report. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Patient Consent

Patient consent was obtained for this case report.