Introduction

At least 4.5% revisit the emergency room (ED) four or more times per year and account for 21% to 28% of all ED visit.1 Another study found 7.5% of patient ED revisits were within 72 hours.2 ED revisits are strongly associated with increased hospital readmissions, particularly within 30 days. Hospital readmissions can compromise patient care by increasing the risk of complications, emotional distress, and unfavorable health outcomes.3 They also impose financial burdens, as Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program.4 may reduce hospital reimbursements by up to 3% for excessive 30-day readmissions.5 Since medication non-adherence contributes to nearly half of all treatment failures and elevates the likelihood of readmission, strategies like bedside dispensing and tele-pharmacy can play a critical role in minimizing preventable returns. One study on the Meds to Beds program found that parents reported the program significantly improved the transition home by boosting their confidence and understanding of medications, while also reducing stress related to obtaining medications for home use.6 Many community pharmacies are closing or decreasing hours due to an overburdened workforce, shrinking reimbursement rates for prescription drugs, and limited opportunities to bill insurers for services beyond dispensing medications.7 Automated Pharmacy Systems (APS) or Kiosks can provide a solution by being accessible while extending hours to increase access to those patients.

According to Chancy et al., the barriers to adherence among these patients included: 32% who forgot, 18% who cited cost concerns, 11% who faced transportation issues, 4% who refused, 16% who gave other reasons, and 19% who could not be reached.8 Assessing pharmacy hours and access to pharmacies was a limitation of the study. The relationship between access to pharmacy and medication adherence is significant.9–13 Clinical consultations led by pharmacists have demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing patients’ adherence to their prescribed medication regimens.9 The CDC leverages the CPSTF recommendation to promote tailored, pharmacy-based interventions aimed at preventing cardiovascular disease. Highlighting the cost-saving nature of these interventions not only strengthens their impact but also presents a compelling opportunity to engage hospitals through financial incentives.10 Effective interventions include medication education, treatment optimization, and helping with access.11 Causes for ED revisits were recurrence of the same complaint was the highest among patient-related factors (80.5%), inadequate management and no improvement of symptoms in 71.3%.13 Patient related factors included recurrence of same complaints, medication adherence, no improvement of symptoms, and complication of a disease.

The data strongly supports the hypothesis that improving prescription fulfillment, especially through Kiosk models and meds-to-beds programs, can reduce ED revisits. The Kiosks can be patient or nonpatient facing and can be located in physician offices, medical office buildings, hospitals, or as listed by regulatory bodies where medication access can be increased for patients. Medications are prepackaged as part of a formulary, prescriptions are verified by a pharmacist remotely, and pharmacists are available for retail counseling. The stakeholder or consumer would arrive at the device to retrieve their medication, pay, sign for the prescription, and have the right to counseling. The purpose of this analysis is to compare the prescription abandonment rate (PAR) between Kiosk and Non-Kiosk (NK) users in an off-site emergency department (OSED) and a campus ED (CED) that would increase medication access and compliance.

Methods

The analysis took place in a 24-Bed OSED and a 20-Bed CED of an eighty-bed hospital in Central Florida. The OSED sees over 25,000 patients and sends over 37,000 prescriptions annually. The CED sees over 27,000 patients and sends over 32,000 prescriptions annually. 40% of the patient population at the OSED is Medicaid/Self-Pay and for the CED the Medicaid/Self-Pay population is roughly 15% while having similar acuity levels. The study is a retrospective quality improvement project and chart review conducted between February 12th, 2025 to March 26th, 2025 for the OSED and April 9th, 2025 to May 21st, 2025 for the CED. Time ranges were selected for the first six weeks the Kiosks were implemented at either site.

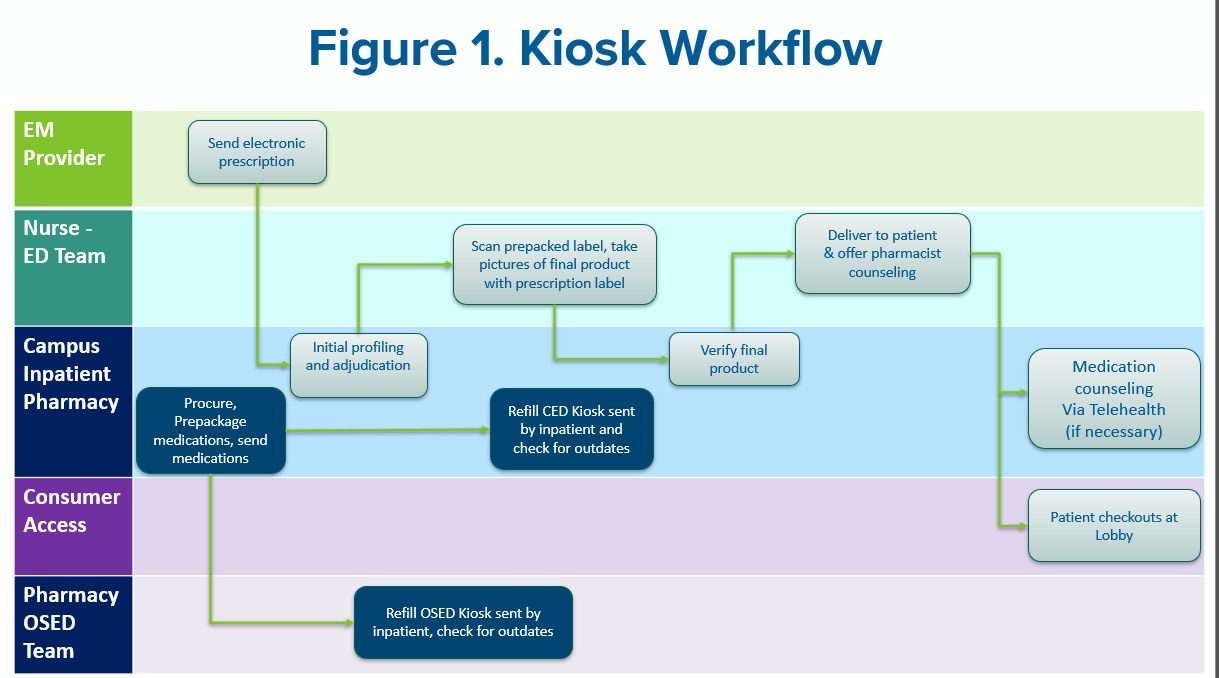

Both EDs launched their 24/7 self-pay meds to beds program by utilizing pharmacy Kiosks to see if it would have an impact on prescription abandonment. The cashless nonpatient facing workflow is shown in Figure 1, formulary, and write-off/comp protocols shown in Table 1. For the pilot, the teams elected to use a self-pay model to prevent delays in discharge. The workflow included pharmacy, nursing, physicians, and patient financial services (PFS). Adherent 360 was the APS used. The APS is composed of a Kiosk dispensing device that interacts with the APS application. Inventory management, pharmacist work, dispensing, financials, and compliance are all done through the application separate of the EHR. Through the interaction of the application, the Kiosk releases prepackaged formulary medication as a medication delivery device. The APS’s workflow is described further in later sections. Kiosk use, age, gender, ED visit history within 90 days, prescription sent after local pharmacy hours, and payor were the baseline items collected. The primary endpoint was the PAR between Kiosk and Non-Kiosk (NK) Users. Secondary endpoints included ED revisits within 3 days, ED revisits within 30 days, discharge disposition to discharge turnaround times, and self-pay prescription capture rates.

Formulary & Inventory

The formulary was decided using historical prescribing trends at both locations. The emergency medicine physician teams approved and standardized medications, quantities, and interchanges. The medications were loaded if the approved quantity was commercially available or prepackaged with the approved quantity in a 30 – 60 dram bottle that can fit in the APS. Prices were based on a blended 340B and wholesaler acquisition cost (WAC) pricing plus $5. See Table 1 for the complete formulary. The APS can hold 700 - 800 units of product and was affiliated with the campus’ outpatient pharmacy in compliance with statutes.14 The inpatient and OSED pharmacy team was responsible for prepackaging, refilling, and outdating the Kiosk.

Workflow & Staffing

At discharge, nurses and providers would request if the patient would like to participate in the ED meds to beds program. If the patient opted in, the provider utilized the approved Kiosk order sentences in the EHR. The inpatient pharmacist covering would verify the prescription and notify the nurse in the EHR that the medication is ready for release. Then, the nurse would retrieve the medication from the Kiosk workstation, scan the prepackaged label, take photos of the bottle with prescription label for the pharmacist to verify remotely, and compile medications into prescription bag with the receipt. Once the pharmacist completed the second verification, they notified the nurse and PFS that the patient was ready for checkout. The nurse would deliver the medication with their discharge paperwork and escort the patient to checkout. PFS would collect the signature, payment, and check the patient out. If counseling was required, the nurse, provider, or PFS would contact pharmacy via phone and the pharmacist would speak to the patient.

Patients that received a prescription were included in the analysis. Due to regulations, the APS did not release any controlled substances. To collect the primary endpoint, a medication history technician followed up with the NK patient’s community pharmacy to confirm if their prescriptions were picked up. Patients were not included in the analysis if the technician was unable to reach the users’ outpatient pharmacy for NK patients. Secondary endpoints were retrieved through retrospective chart review. The required sample size was calculated to be 120 patients, with a margin of error of 7% and a 95% confidence interval. Chi-Square statistical tests were used for the primary endpoint of prescription abandonment.

Results

The OSED had 2,999 ED visits where 4,500 prescriptions were provided and a Kiosk prescription capture rate of 10%. The CED had 2,797 ED visits where 3,689 prescriptions were sent and a Kiosk prescription capture rate of 15%. After randomization, 30 OSED Kiosk patients, 30 CED Kiosk patients, 57 OSED NK patients, and 30 CED NK patients were reviewed to make a total of 147 patients. 27 patients in the OSED NK group did not meet criteria due to outpatient pharmacy follow up on prescription abandonment. 120 patients were included in the analysis. The baseline demographics and results are shown in Table 2. 60 Kiosk patients obtained all their prescriptions while 30% of NK patients (18/60) abandoned their prescriptions (P < 0.05). One Kiosk patient and three NK patients revisited the ED within 3 days. Both groups experienced 9 ED revisits within 30 days. The average disposition to discharge time was 31.5 minutes to 21.1minutes for the Kiosk and NK patients respectively. Both arms had similar patient populations except for an increased history of ED revisits within 90 days (38.5% VS 26.7%), after hour pharmacy prescriptions (38.3% VS 26.7%), and Self-Pay patients (26.7% VS 20%) in the Kiosk arm.

Discussion

Implementation of pharmacy Kiosks in OSEDs and CEDs has significantly reduced prescription abandonment. The study also found a 3.3% reduction in ED revisits within 3 days. Of the 33% of the NK patients that abandoned their prescription, the prescription was sent during their pharmacy’s after hours. This was recently highlighted in Chancy, et al’s study.5 With the addition of Kiosk to the ED team’s workflow, the patient’s average disposition to discharge time was roughly 10 minutes longer to their stay (31.5 minutes VS 21.1). On average, during the study, 77% of the prescriptions sent from the OSED and CED were available formulary items in the Kiosks. The write-off/comp protocol was used for 29% of total OSED Kiosk patients versus 24% of total CED Kiosk patients. In this protocol, the prescription fee was waived or covered by the health-system if one of the following: Provider or nurse leader wishes the patient to go home with medications due to risks of adherence or compliance, Patient being discharged when their retail pharmacy is closed and patient opted to use Kiosk, any downtime during collections or if the patient only had cash. With having the goal of increasing medications access to patients, we believed protocol use was appropriate during this study.

The ED physician, nursing, and PFS staffing models between the OSED and CED did not change but included the Kiosk workflows. Traditionally, for pharmacy, the campus inpatient pharmacy team provided oversight of the OSED. The campus inpatient pharmacy team verified orders, and the mobile OSED pharmacy team visited the OSED twice a week for automated dispensing cabinet replenishment. For Kiosk implementation, the campus pharmacy team was responsible for prepacking and served as the central inventory for both the OSED Kiosk and the CED Kiosk. For this, the pharmacy team earned 0.5 pharmacy technician full time equivalent (FTEs) for each Kiosk for prepackaging and Kiosk inventory. The pharmacy team used 0.2 pharmacy technician FTE for a capture rate of 10% and up to 0.5 FTE for a capture rate of 30% for labor expense and productivity. The campus pharmacy team would send the prepacked formulary medication to the OSED for the mobile OSED pharmacy team to replenish the Kiosk.

The campus pharmacy team replenished their own Kiosk in the emergency department. Like the ED physicians, nursing, and PFS, the work for Kiosk prescription verification for the pharmacist was absorbed in the workflow. Prescription verification was accomplished and prioritized by the ED pharmacist and central pharmacy when ED shift was flexed. The average prescription turnaround time for the pharmacist was 6 minutes (4.1 for initial drug utilization review and 1.9 minutes for photo quality assurance verification). An increase in pharmacist interventions took place because the pharmacist had access to the patient’s EHR. Therapy recommendations, antimicrobial dosing, drug-drug or allergy interactions, and therapeutic interchanges were the most common inpatient pharmacist interventions on outpatient prescriptions. For compliance, statutes for APS use in different states may vary. A Risk-Based Analysis was conducted that assessed possible regulatory violations and medication safety events.

Lessons Learned, Opportunities, and Limitations

Due to the Kiosk’s ability to operate 24/7 without any physical pharmacist presence, it required a significant amount of collaboration with pharmacy, nurses, providers, and PFS. The APS was separate and did not interface with the inpatient EHR. Therefore, nursing, pharmacy, and PFS were trained on the new system four weeks prior to go-live. Figure 2 shows the lessons learned and the action items to improve the process moving forward. Provider workflows, Kiosk scripting to patients, payment conversations, and workflow communication were the processes that required improvement after go-live.

Historically, physicians would use their own prescription favorites in the EHR and sent the prescriptions to the patient’s preferred pharmacy. Now at discharge, they needed to request if the patient wanted to participate in meds to beds, confirm if the prescription is on formulary, then utilize the Kiosk prescription sentences in the EHR. During go-live, a pharmacist would review possible ED discharged patients and partner with the provider on possible Kiosk use. Also, data was provided to physician leadership for targeted education and follow up.

Scripting and payment conversations served as a challenge for each of the team members because meds to beds processes were owned by the campus retail pharmacy teams. The nursing teams were asked upon patient arrival to bring awareness to the Kiosk meds to beds program. Patient flyers and resources were provided to support the teams. When scripting took place, it led to difficult conversations for nursing, providers, and PFS because the program was self-pay and patients wanted to utilize their insurance. As a result, patients would opt-out of the meds to beds program and led to team member dissatisfaction. After receiving feedback from the stakeholders on this concern, the teams elected to utilize insurance since the APS was able to incorporate real time adjudication that wouldn’t cause discharge delays. See Figure 2 for complete action plans on scripting and payment collections.

Due to the lack of EHR interface, remote verification, and multiple stakeholders in the workflow, communication was an area of opportunity. The pharmacy team communicated to nurses through the EHR and to PFS through the health-system’s approved chat system. The pharmacist communicated to the nurse when the medication was ready for retrieval and delivery. Lastly, the pharmacist messaged PFS when the patient was ready to be checked out. There were instances where team members were pulled into patient care and troubleshooting. This caused delays because the messages were going unread and required escalation. As an area of opportunity, the APS is developing a centralized communication tool and tracking system to overcome this barrier.

The project and analysis had limitations. A larger sample size would have increased reliability and validity to the results. Another limitation was the assessment of the reason for the ED revisits or the reason for prescription abandonment. Statutes or legislature may vary by state on Kiosk formularies and practices which can pose as a challenge. Lastly, the study’s self-pay model for the meds-to-beds program posed as a barrier, as patients were unfamiliar with this model and preferred to use their insurance, leading to dissatisfaction and opt-outs. These limitations highlight areas for improvement in future implementations of pharmacy Kiosks and similar interventions.

Conclusion

The is the first analysis to introduce a 24/7 ED Meds to Beds program with automated Kiosks. The project was able to demonstrate a collaborative workflow between physicians, nursing, pharmacy, and PFS so patients can retrieve their discharge medications in the ED. The study found that the Kiosks significantly reduced prescription abandonment rates and slightly decreased ED revisits within three days. Future studies are warranted for different APS systems, workflows, adjudication processes, and patient experience.

Conflicts of interest

None

# IRB APPROVAL

Obtained at local institution

Funding

None

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CREDITS

None